DIY Faraday Isolator

For a discussion of the motivation behind Faraday isolators, please see the section on frequency-stabilized lasers. The following is a guide on how to fabricate a low-cost alternative to commercial Faraday isolators (typically >$1000 in cost).

A Faraday isolator utilizes the Faraday effect and the polarization of light to allow the transmission of light in only one direction. Thus, the four main components of a Faraday isolator are: an input linear polarizer, a strong magnetic field, a nonlinear optical crystal, and an output linear polarizer.

Theory

The Faraday rotator is comprised of the magnetic field and the nonlinear optical crystal. The optical crystal is oriented within the magnetic field, such that its optical axis is parallel to the direction of the magnetic field. Then, as light passes through the crystal, its polarization state is rotated by an angle:

\[\theta = VBL\]

where \(V\) is the Verdet constant of the crystal, \(B\) is the magnitude of the magnetic field within the crystal (assumed to be constant), and \(L\) is the length of the crystal.

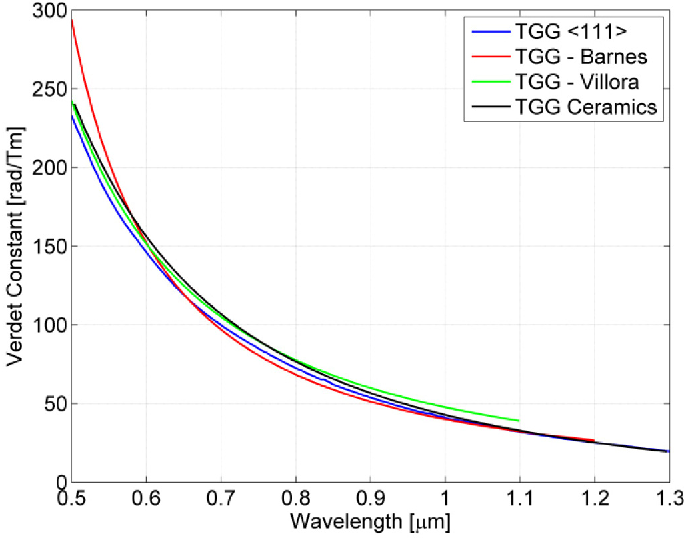

The Verdet constant is a material property, and is typically very low for most crystals - the discover of novel materials that enable Faraday rotation is an active area of research. Moreover, the Verdet constant is wavelength (and temperature) dependent, meaning that a different magnetic field strength and length will be required for different light sources.

One of the most common materials used for Faraday rotation is terbium gallium garnet (TGG). This crystal has a very high Verdet constant - approximately 61 radians per meter-Tesla at 780nm. Thus, to achieve a 45 degree (0.785 radian) rotation (the necessary rotation for optical isolation), we require 0.0128 meter-Teslas. Since magnets are much cheaper than TGG, we utilize the strongest ring magnet we can find, thus reducing the necessary length of the TGG crystal.

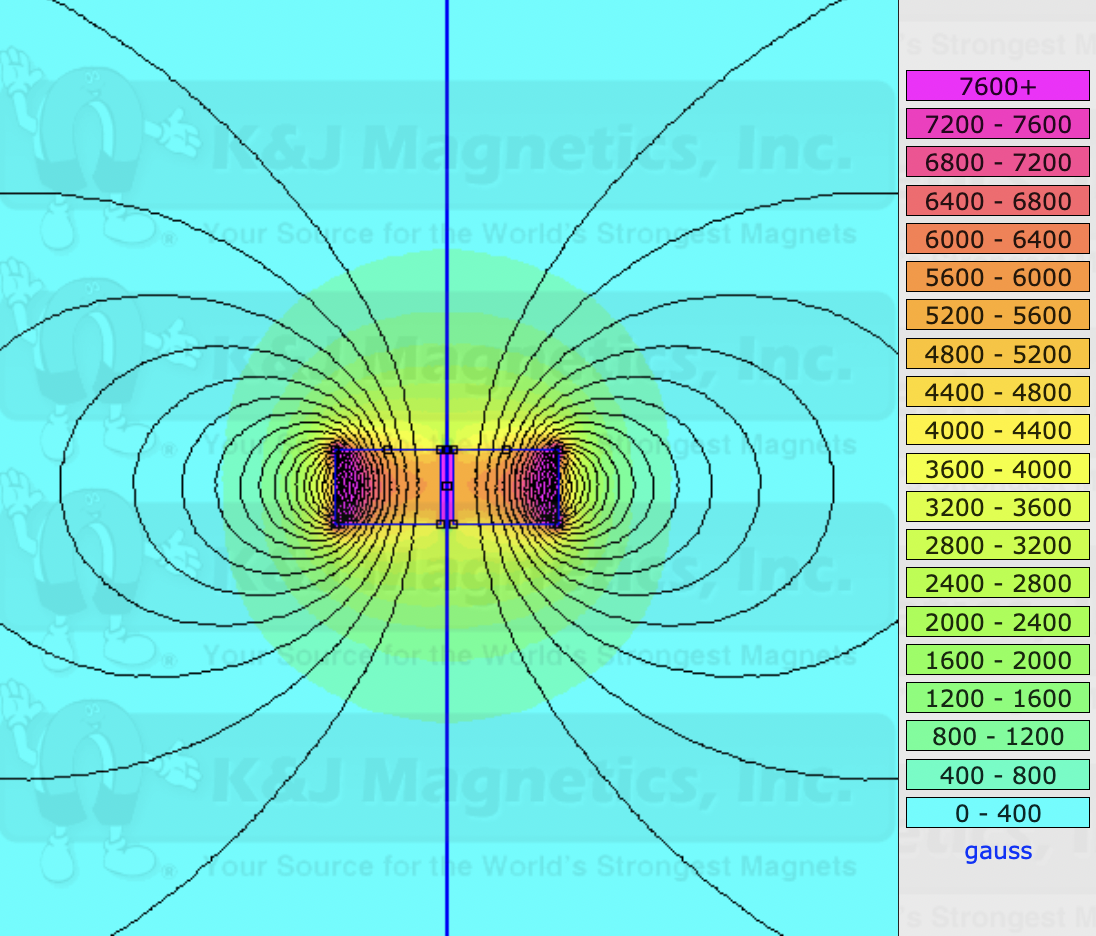

For this purpose, we utilize the two of the K&J Magnetics RX828, which is a 1.5 inch outer diameter, 0.125 inch inner diameter, 0.5 inch thick axially magnetized ring magnet. According to a finite elements simulation, the magnetic field magnitude along the central axis of this magnet is roughly 0.64 Tesla. Therefore, we require a 20mm long TGG crystal to complete the Faraday rotator (0.0128 meter-Tesla / 0.64 Tesla = 0.02 meter).

Fabrication

Tools Required

- FDM 3D Printer

- SLA 3D Printer (probably optional)

- Epoxy

Bill of Materials

Purchase

- K&J Magnetics RX828 x 2 ($23.24 x 2)

- Terbium Gallium Garnet, 20mm length x 2mm diameter (~$100)

- Linear Polarizers x 2 ($15 x 2)

Assembly

The fabrication of the optical isolator is remarkably simple. I purchased the TGG crystal from Crystro, a Chinese manufacturer, for about $120 (I am not affiliated with this company in any way - but to note, North American manufacturers quoted me $600+ for the same crystal).

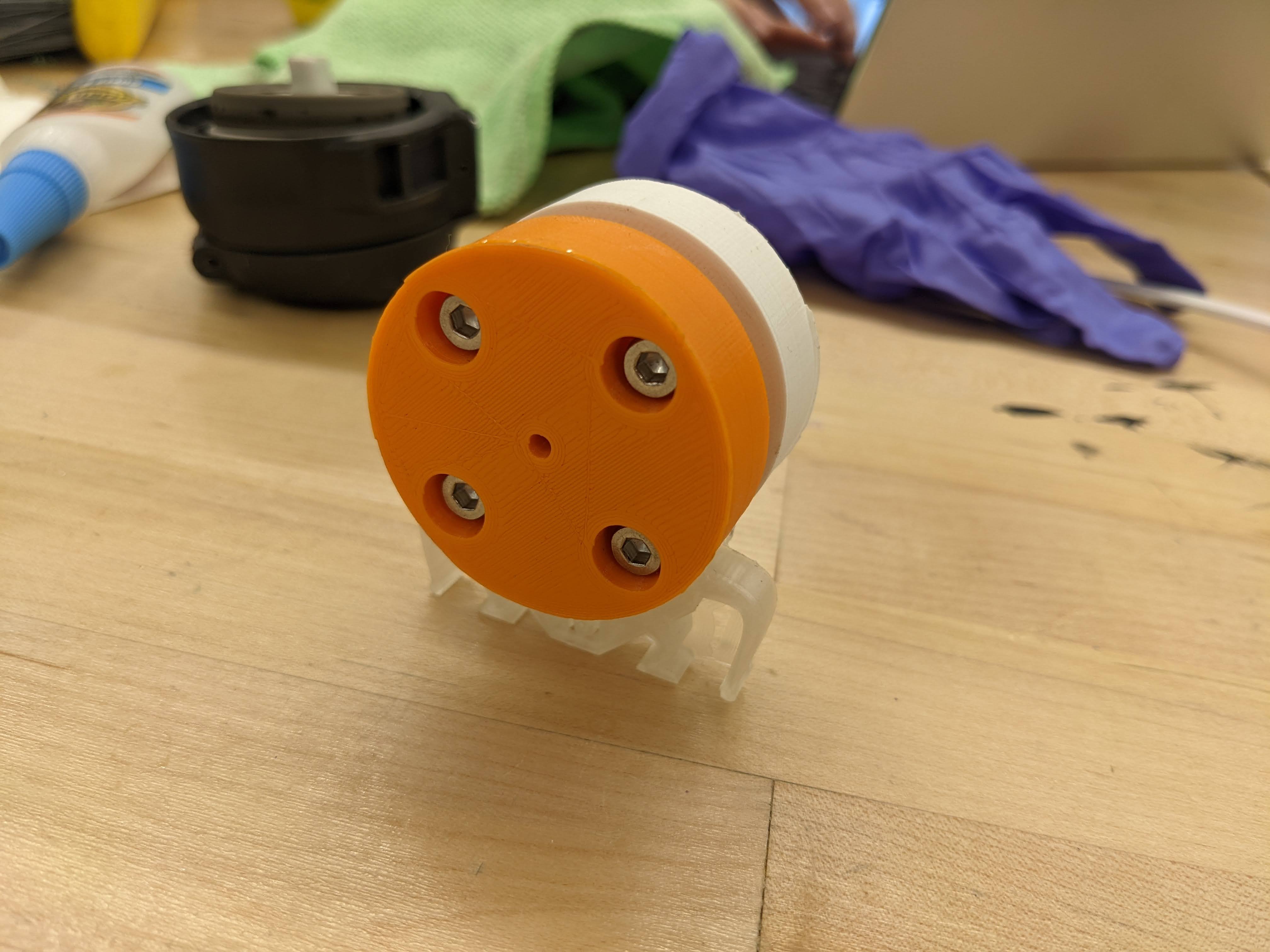

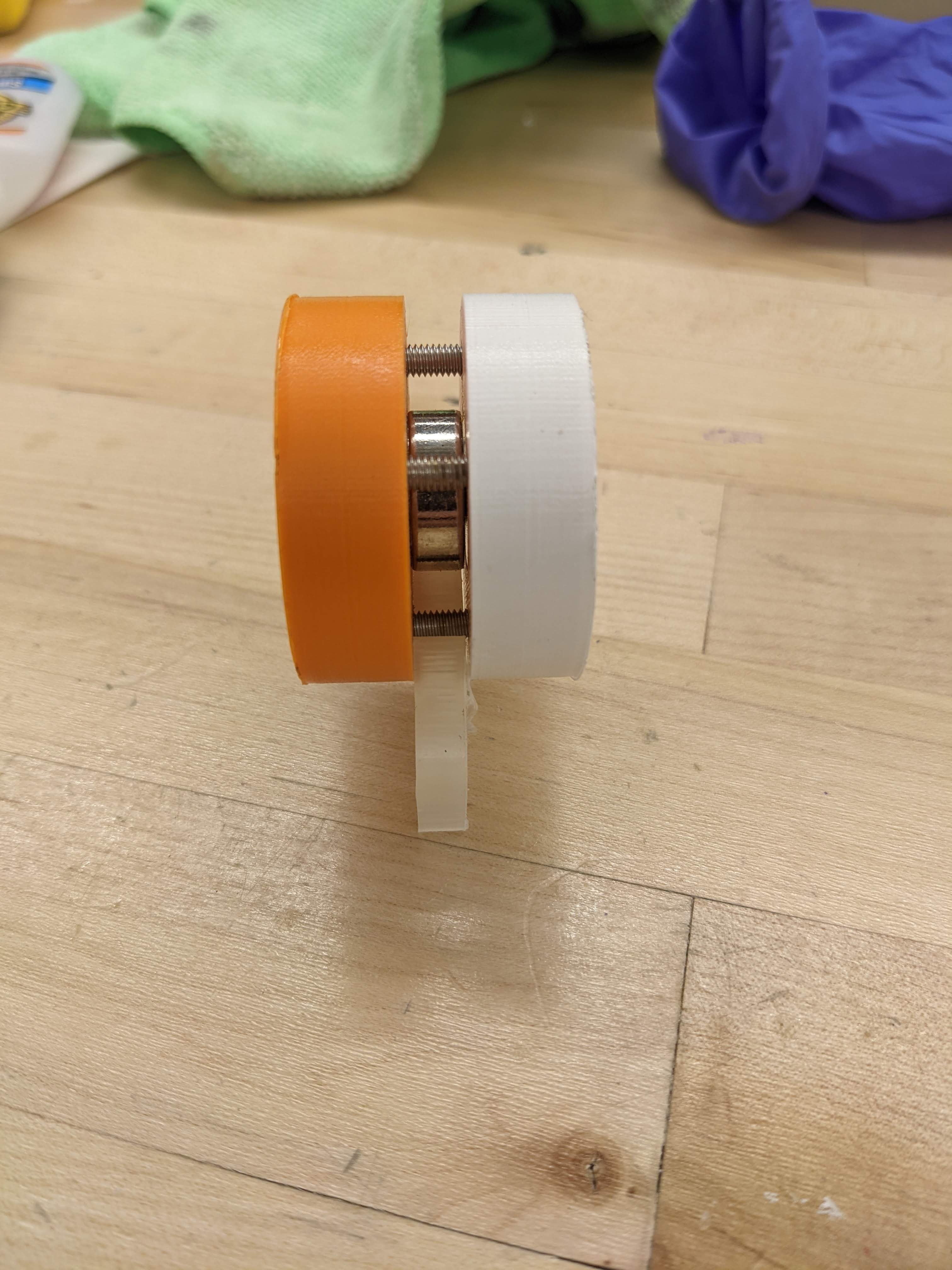

The TGG crystal must be inserted down the hole of the ring magnets; for this, I used a 3mm outer diameter, 2mm inner diameter resin sheath 3D printed on a Formlabs Form2 SLA printer. The resin sheath has a small hole in the side that can be used to epoxy the crystal in place without fear of damaging the optical surfaces. I rely on the tension fit between the sheath and the inner diameter of the magnets to hold it in place. This should be quite secure unless you are shaking the rotator violently (not recommended) or pushing on the sheath with tweezers.

I mounted the magnets in two 3D printed covers. In hindsight, I regret doing this, because it made the device much bigger than it needed to be. However, this also allows me to mount it on an optical post, which can then be put on a breadboard.

To complete the Faraday isolator, we need two linear polarizers. These are commonly available on eBay for about $15 each (although this is also highly dependent on the wavelength of light you are using). The polarization axes of the polarizers must be offset by 45 degrees. When these are mounted on either end of the rotator, light should only be able to travel through in the direction of the magnetic field!

With my build, I achieve roughly 45% transmission and 32dB isolation using a 200mW 780nm laser. A possible cause of the relatively low transmission is due to the fact that my laser beam is likely diverging before exiting the rotator (due to its relative long length and small diameter); better beam tightening and collimation may lead to better transmission.